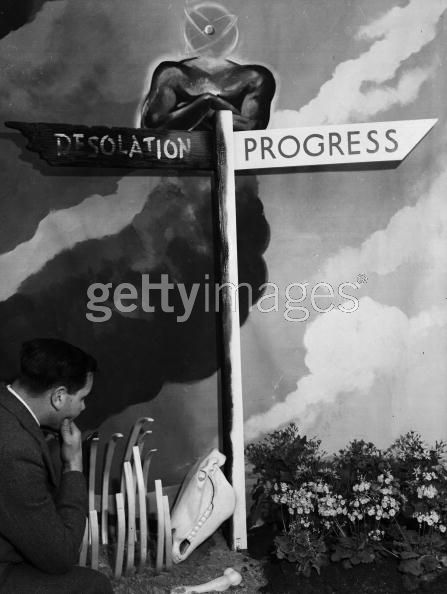

Disillusionment and Demise

By the mid 1960s, it had become increasingly clear that the grand dreams of the atoms for peace movement would not be easily realized. Ocean liners were not running on a thimble-full of fuel, there were no atomic cars, electricity was not free, and irradiated super plants had not eradicated famine. Public opinion had generally rejected the concepts that the dangers of nuclear power could be ameliorated by its benefits–however peaceful–and attitudes of protest and pessimism held sway.

For the amateur atomic gardeners, atom-blasted seeds hadn’t even produced anything that interesting in their own backyards. The obvious problems of proper controls and careful gathering of data that still plague attempts to crowdsource science today couldn’t be overcome by the Atomic Gardening Society or by C.J. Speas, and their attempts to coordinate with established scientific research efforts were rejected.

Individual gardeners likely became impatient with the breeding through successive generations that was required to produce a truly viable mutant, and with seeds that were more likely to not germinate at all than to produce tomatoes of enormous size .

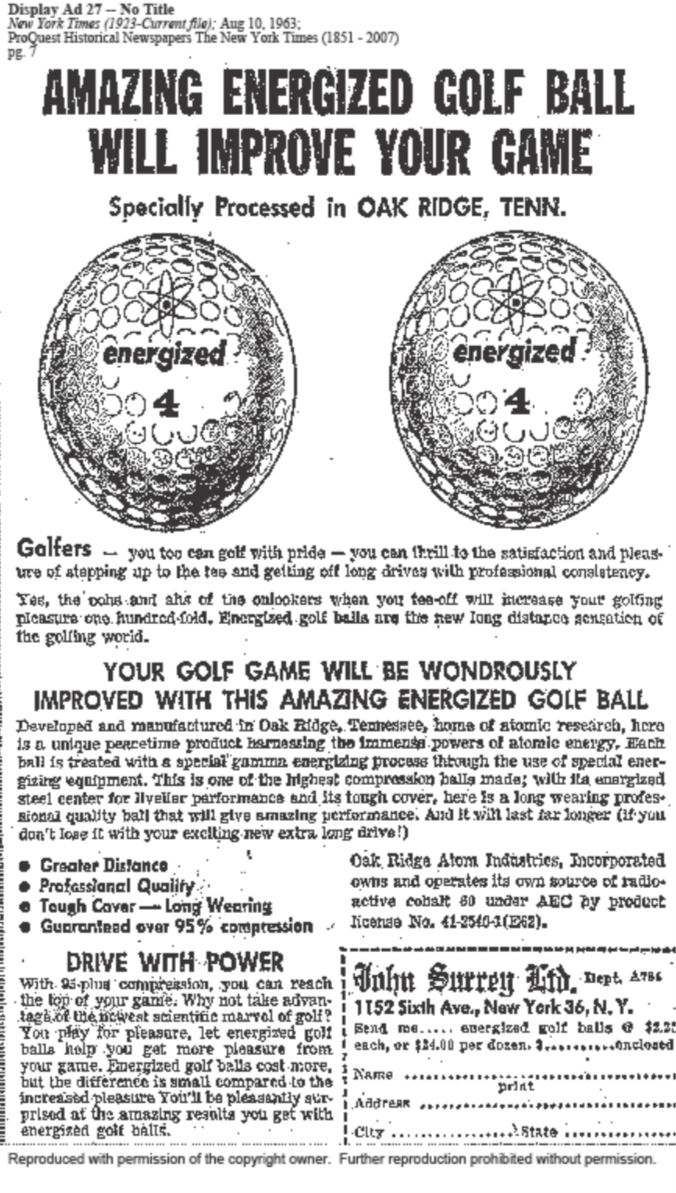

By 1962, advertisements and mentions of C.J. Speas atom-blasted seeds had disappeared, and by 1963 he was turning his bunker to irradiated golf balls. (1)

And as for Muriel? When she formed the Atomic Gardening Society in 1959, Muriel was already 78. Her eyesight was failing, and her unusual career of atomic advocacy was coming to an end. By 1962, she had turned over the society to a new president, Dr. T.E. Gray, a retired geneticist who had studied with Luther Burbank and specialized in tomatoes. She most likely also turned over all of the society records to him, and they have not been found.

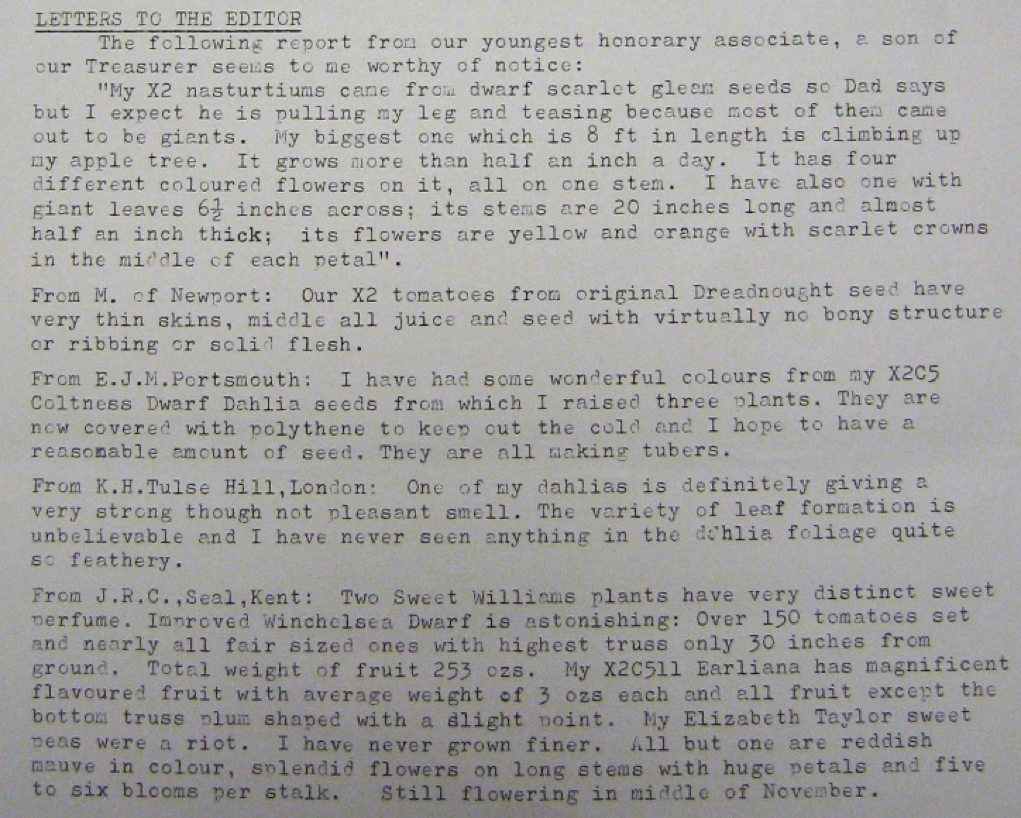

At least in 1962 the gardeners were still reporting from anonymous suburban gardens on their giant nasturtiums, strange smelling dahlias, and sweet peas flowering in mid-November, atomic progeny all, but the last archival presence of the society that I have been able to find is from mid-1963.

Last known record of the Atomic Gardening Society’s activities, 1962